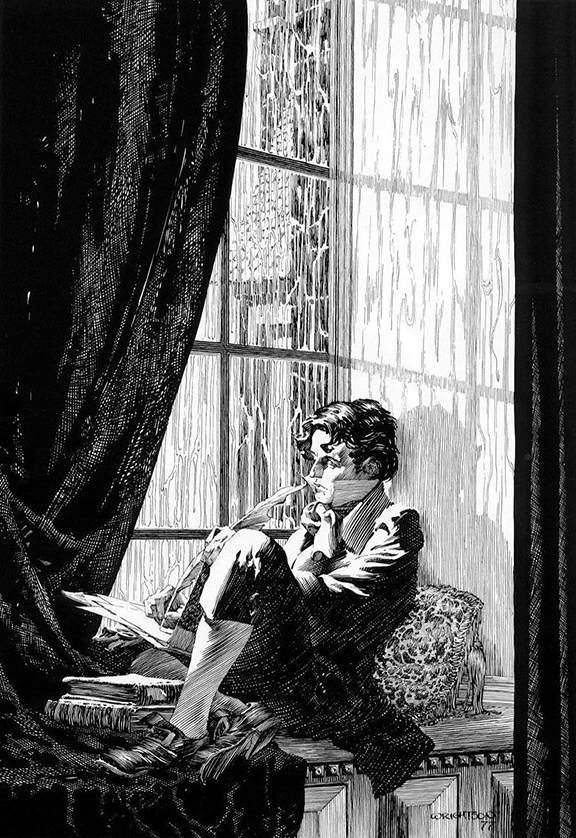

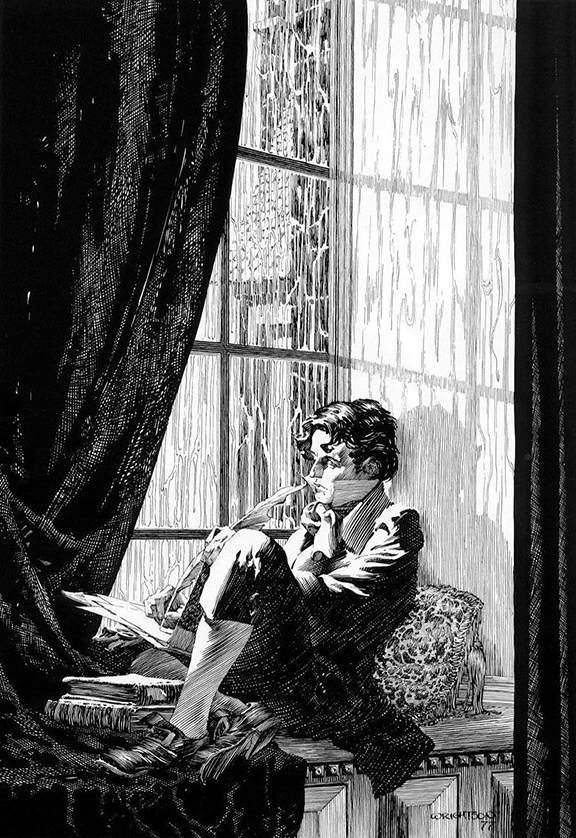

Bernie Wrightson

Bernie WrightsonHe may just be half a century earlier qua timestamp, but still fits this book quite nicely

Bernie Wrightson

Bernie Wrightson

He may just be half a century earlier qua timestamp, but still fits this book quite nicely

Naar vriendschap zulk een mateloos verlangen ,

the tekst on our national homomonument in Amsterdam

is a quote from the poem:

'Aan eenen jongen visscher' (to a young fisherman)

by Jacob Israël de Haan:

|

Rozen zijn niet zoo schoon als uwe wangen, Tulpen niet als uw bloote voeten teer, En in geen oogen las ik immer meer Naar vriendschap zulk een mateloos verlangen.

Achter ons was de eeuwigheid van de zee,

Laatste dag samen, ik ging naar mijn Stad.

Ik ben zóo moede, ik heb veel liefgehad. | Roses are no match for the cheeks you turn tulips don't compare your naked feet on the floor and in his eyes I always read more for friendship such a fathomless yearning |

longing

verlangen, hunkering

demand

vraag, verlangen, vordering, eis

hunger

eagerness

gretigheid, verlangen, begeerte, vurigheid

anxiety

angst, bezorgdheid, ongerustheid, zorg, benauwdheid, verlangen

hanker

verlangen

yen

yen, verlangen

desire

verlangen, wensen, begeren, verzoeken, verkiezen, trek hebben in

demand

vragen, eisen, verlangen, vereisen, vorderen, vergen

wish

wensen, verlangen, toewensen, begeren, verkiezen, trek hebben in

yearn

verlangen, hunkeren, reikhalzen, smachten naar, zich aangetrokken voelen tot

want

nodig hebben

the word Sehnsucht is German for 'aspiration' or 'longing.', see monument data.

Some more bio info on de Haan from a Volkskrant review:

Author of two scandalous novels, poet, lawyer, journalist, homosexual,

engaged jew, who in the end got assasinated by a Zionist

- in his biography on Jacob Isra l de Haan ,

Jan Fontijn leaves the final judgement to the reader.

By: Aleid Truijens 23 mei 2015, 02:00

His death got far more publicity than his life and work ever did.

His murderer was Avraham Tehomi, a 21-year old subcommander of the paramilitairy Zionist organisation Haganah.

In the year of his death de Haan's poetry collection 'Kwatrijnen' got published.

Resteless soul :

On june 30, 1924, in Jeruzalem, three gunshots made a brutal end to the life of a 42 year old Jacob Isra l de Haan.

Some years before the poet, novelist, lawyer and journalist De Haan had left full of idealism for Palestine.

He soon got disenchanted. He saw the hatred between Arabs and Jews and between Zionists and orthodox Jews.

THe order came from his boss, Ben-Zwi, later Isra li president, who persevered in denying his involvement.

The dangerous element and threat, that De Haan posed, writing for Dutch and British newspapers,

in which he sharply critisized the zionists, had to be liquidated, was the general opinion within Haganah.

This first political murder in Palestine, shocked the world.

Biographer Jan Fontijn, calls the four line poems the "diary of his inner life".

That sure is a way you can read these melancholic, clear and sometimes mocking verses.

They brong the tormented writer, always strugling with guilt and penitence,

with a god that might or might not exist, homesick desire, lustfor beautiful boys always there,

Most known got to be his quatrain 'Onrust' (unrest), of which the biographer took the title:

"Die te Amsterdam vaak zei: 'Jeruzalem'

En naar Jeruzalem gedreven kwam,

Hij zegt met een mijmerende stem:

'Amsterdam. Amsterdam. ' ""who in Amsterdam often said: 'Jerusalem'

and was driven there,

he keeps saying in musing voice:

'Amsterdam, Amsterdam' "

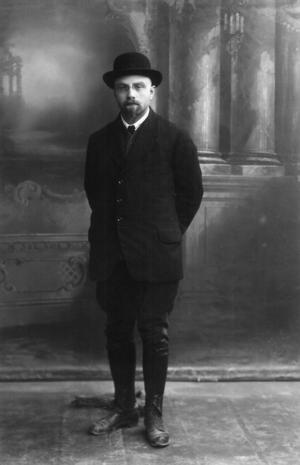

Jacob Israel de Haan in a Parisian photostudio, somewhere around 1919. © Bezige Bij

but barred by te injustice he meets underway that has to be put right first.

A soft and dedicated friend, but also uncompromising. Someone who easily makes ennemies.

"He had a huge heart, panting for justice", a riend said.

Even though the chronicles he wrote for Algemeen Handelblad were well read,

and two 'homosexual novels, Pijpelijntjes (1904) and Pathologi n (1908)

caused an enormous uproar,

he remained a sideline figure in Dutch literature.

His sister Carry van Bruggen got far more public acclaim.

Unheard of in those days, de Haan in his two novels wrote frankly

about the love relationship between two young men.

True promotion or a commercial advertizement for 'the love of men' he surely did not make:

sadism and masochisme play pivotal roles in both the novels.

As a result the author got himself nailed to the pillory.

In the SDAP, where he was active during his years as young school teacher,

he got vomitted out:

P.L.Tak, chief editor of the socialist daily Het Volk,

discharrged him from writing the childrens column in that paper.

He was left only with some temporary jobs in the city's education office,

M.D. and writer Arnold Aletrino,

who recognised himself as a main character in Pijpelijntjes was furious.

He bought the entire first edition, in order to destroy them all.

De Haans best friend, writer and psychiatrist Frederik van Eeden,

who he idolised, found both novels 'horrific',

too filthy to read out untill the end...

Obviously he hated being portrayed as the politically correct but oh-so bourgois scientist,

who had great theories about homosexuality,

but failed at living that out in a fullfilling way as practicing out homosexual.

Hype

Pathologie n has a subtitle that leaves us with very little hope:

'The decline and fall of Johan van Vere de With'.

In 1975 this unusual novel, in which a satanic lover

destroys the art-loving boyfriend and object of his lust.

Just as Pijpelijntjes causing a hype, especially amongst Neerlandici.

UvA-teachers Leo Ross en Rob Delvigne, who had rediscovered his work,

wrote highly exiting articles about them,

causing the issue of quite a number of new editions of both.

Even De Haans poetry enjoyed new prints.

He always kept admirers; his life and death inspired many other artists.

He was the son of a Chazan, a master of ceremonies in the synagogue, who grew up in Zaandam.

a Sensitive, smart boy who admired his wise father

and always hanging out with his one year older sister Carry.

Fontijn shows us a writer who yearns back to the days of warm family life

and self-evident piety radiating from his parential home.

He married, with doctor Johanna van Maarseveen;

a childless marriage of friendship and convenience,

even though he dearly wanted children.

And so he moved to Palestine, without her.

How De Haan's love and respect for his father,

his childlessness and love for boys, gel together,

is not psychologically analysed by Fontijn,

but he does show the connection.

Compassion and understanding

The biography is written with that in mind for the subject person,

without the biographer crawling too deep within the skin of him.

There remains a healthy distance to get to grips with such a life full of contradiction.

Fontijn refrains from giving many comments on the material that he's uncovered:

letters, newspaper clips, but also the earlier books on De Haan;

he leaves any judgement to the reader.

It looks like there just was nothing that could go right in this life.

De Haan really was a malapert homosexual,

who later on did get to feel ashamed about the 'sins' committed,

a convinced socialist and zionist, who just was forced into resentment of his former allies.

He returned to the faith of his youth, became pious, but kept on doubting their 'god'.

In the end

a catholic writer, an Arab boy and an orthodox-jewish docter remained his closest friends.

with this book Fontijn fulfills a promise that the subject of the first biography he wrote,

Frederik van Eeden, had, unwittingly, given him:

In a tribute after his death Van Eeden expressed the wish that there would be :

"a life description of Jacob Isra l; a deep digging study,

'worthy of such a sensitive author' " .

also need to add a commenton many of the biographers of de Haan by my 'Softies' buddy since the late 70's:

Michiel Bollinger, who laments on how most bio's come from the orthodix Jewish community,

a section of our population that's not known for their tolerance, so they tend to ignore his homosexuality,

if not even call it the cause of his pro Palestinian inclinations and his death.

You can find the Dutch version on his wordpress pages,

but I felt it wiser to give you an English translation here:

MY CRITICISM on JAN FONTIJN'S BIOGRAPHY about the poet JACOB ISRAEL DE HAAN (1881-1924)

DOODSDRIFT OF VERRAAD.

In the foreword, Jan Fontijn states that he sees the biography as an 'instrument of historical justice'.

He will write this book about Jacob Israel de Haan

'to correct or nuance the image that others have claimed about De Haan's life and personality'.

He does this through thorough source research

and by maintaining 'the circle of uncertainty and indeterminacy and enigma' of life as much as possible.

Fontijn goes in search of the 'floating, hidden forces in De Haan's life'. Where does he come from?

Nest polluter

After reading the biography, the image of Jacob Israël de Haan predominates as a quarrelsome man with a death drive,

a Jewish man who loved Palestinian boys too much, a sadomasochistic aesthete who mixed love with death wish

just as easily as poetry with politics.

That could lead to nothing but his violent death. At least that is how Jan Fontijn describes De Haan's life:

a tragedy in which fate unfolds step by step, ultimately resulting in the fatal pistol shots on 30 June 1924.

A young member of the Zionist underground resistance movement later confessed to the assassination attempt.

De Haan was considered too dangerous by the Zionists, he was a spokesman for the anti-Zionist Orthodox Jews

and a prominent journalist in Dutch and English magazines. The nest polluter had to be eliminated.

You can call De Haan a Jewish poet, as he liked to see himself in the 1920s. You can also call him a gay poet-writer these days.

His text is engraved on the Amsterdam gay monument: Naar Vriendschap Zulk Een Mateloos Verlangen.

The fact is that Jacob Israël de Haan played many instruments at different times in his life, usually in a rather high pitch.

That is his appeal, but it also makes it difficult to categorize him unambiguously.

His betrayal

Jan Fontijn tries to fulfill his promise of historical justice by extensively portraying the perspective of De Haan's contemporaries.

In the eyes of many, De Haan is a perverse ( because homosexual ) Jew, so unreliable, a traitor first to the socialist and later to the Zionist cause,

a pederast of a questionable level. Those accusations resound throughout his life. Even after his death, he was ruthlessly judged.

The most colorful was Abel Herzberg, who wrote in 1954: 'He was not a 'Jewish' poet. Not only did he never understand a Jewish mentality,

he also had no part in it. No doubt he was inspired by something like a mother's desire. And no doubt his mother was a Jewess.

But this is coincidental. De Haan was never included in the lifestream that could be called the Jewish one.

He was unable to approach it, and he must have felt it. Hence the cerebral, the forced of his poems. Hence his betrayal.

But all those negative judgments still don't explain why De Haan had to be killed. De Haan was the first deadly Jewish victim of Zionism.

The murder shocked many, in Palestine, the Netherlands and beyond. You can call De Haan naive in retrospect,

but who could have suspected that he, a spokesman for the Orthodox Jews, would actually be shot dead by a Zionist terrorist?

Yes, in the few years he spent in Palestine, De Haan became a leading anti-Zionist. And yes, he received several death threats.

He played high game, but his weapon was the pen. Free speech was his aspiration and passion.

longing for death

Unfortunately, this biography fails to place in historical perspective a poetry that uses the death instinct as its theme,

alongside other themes such as the notion of God, memory, desire, lust and love.

Many of De Haan's contemporaries were supporters of a Freudian theory that is rather old-fashioned today.

Of course, De Haan must also have been aware of the late romantic tradition of the artistic death instinct.

He may have identified himself with it as a poet, but even then a biographer in 2015 should not blindly adopt this as a guideline for a biography.

Jan Fontijn hedges against this criticism by claiming that it is 'tempting to associate De Haan's preoccupation with death,

and sometimes his desire for it, with the controversial theory of the death drive proposed by Freud in 1920

in his writing 'On the other side of the Lust Principle' was developed. That sounds nuanced, and rightly so.

But with the following quote on page 513, Fontijn only confirms this controversial theory by declaring it applicable in its entirety to De Haan:

'Freud linked the death instinct to masochism, which he described as sadism directed against one's own person.

A ruthless conscience (super-ego) is in intense tension with the Ego, resulting in melancholic extreme self-blame and can sometimes lead to suicide.

De Haan's ruthless conscience manifested itself in two ways: socially and psychologically. Social when he made high demands on himself

and his political opponents in the political and social spheres, leading to conflict and eventually even to his death.

Psychologically, his ruthless conscience manifested itself when he made high moral demands in the erotic field

and had to find out more than once that he was deficient, which led to feelings of remorse and melancholic longing for death.'

Heavy words that sound like amateur psychology. The biographer Jan Fontijn confuses a poetic theme (the death instinct) with a historical fact

(the murder of De Haan). And meanwhile, the damage has been done: the biography gives the impression that De Haan himself wanted to die;

that he may not have staged his death himself, but he did provoke it. But De Haan did not provoke his fateful end. Not he but his killer ended his life.

A spirited man

Jan Fontijn seems to have fallen into the pit he dug himself. By not distilling his own modern analysis from historical sources,

he confirms an unjustified, false image of Jacob Isra l de Haan as a poet with a death instinct.

Fontijn has concentrated too much on the judgment of his contemporaries. De Haan's work itself reads like the diary of an enthusiastic man.

He was a troublemaker and his work shows a longing for death and a zest for life. He linked strict religion with rambunctious physicality.

Jacob Israël de Haan fought on many fronts and perhaps that battle was unwinnable.

But how beautiful and sincere are his wise words of joy and sorrow still, one hundred years later?

If there is one advantage of this biography, it is this: his opponents from then sound now petty and insincere. I call that historical justice.

In 1983-1984 Michiel Bollinger staged a music theater program about the life and work of Jacob Israël de Haan.

don't hesitate to suck it to me with questions or suggestions / submissions.

back to the calendar